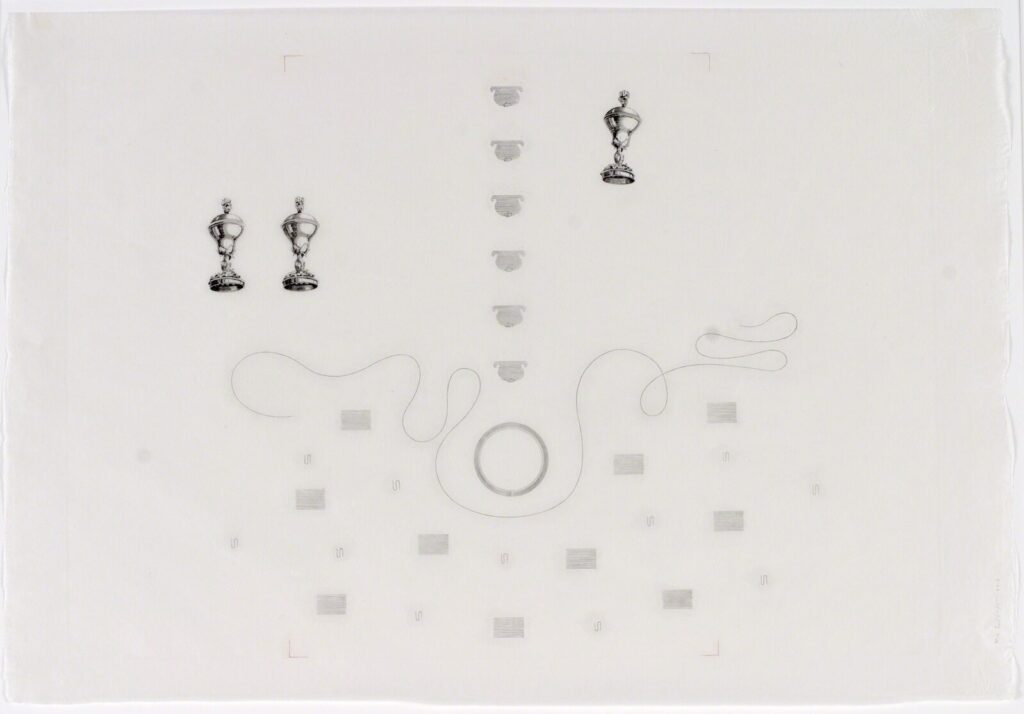

Würth, Anton. DürerÜbung II Nemesis. 2017.

By Sylvie Pingeon

Maybe it’s the compact walls of the Goldrach Gallery, or maybe it’s the show’s refusal to be firmly chronological, but “Engraving After 1900: A Technique in its Time” reminds me of a carousel. A little dizzying, nice to look at, self-serious but also fun.

Only a glass wall, embossed with the exhibition title, separates Pruzan Art Center from the outside world. At midday, this title doubles, as the sun casts the words in shadow on the center’s walls. The gallery space does not have this light, of course. Its dim lighting and pale wooden floors are almost cozy after the stark openness of the lobby. Blocks of texts loosely categorize the pieces: “At Work, At Rest,” “The Natural World,” “Built Environments,” “New Directions.” These labels float a couple of feet above the highest wall-mounted prints. The words hover near the art, suggesting categories but not imposing them. There’s no clear cut-off between one label and the next. The borders between categories meld gently. The prints are arranged anachronistically, but the labels loosely suggest the passage of time, marking a seemingly natural progression. The natural world shifts into a built-up landscape. Eventually, this growth shifts in new directions. The engravings turn experimental, avant-garde.

Supposing a viewer follows this clockwise trajectory, they oscillate between decades: the thirties back into the twenties, a rush forward to the fifties, a push back into the twenties again. Up and down, up and down. A pony on a mounted pole. The exhibition trends towards more recent pieces as one moves left to right across the room, but this trend is not a rule.

The first print seen upon entering the exhibition is Stanley Anderson’s Reading Room. The 1930 engraving depicts an old man poring over a book with an expression that the accompanying text dubs “quiet reflection,” but to me, it seems charged with energy. His lips are pursed, his brow furrowed. In the background, another man bends over a book, his eyeglasses slipping down his face, with his mouth slightly agape. Across from him, a different man slouches over his books, perhaps asleep or perhaps in quiet despair.

The label “At Work, At Rest” reads a little on the nose for this piece. But I don’t mind because the words are far away and easy to ignore. I like Reading Room aesthetically. It’s shaded softly, a gradual scale of light to dark. It holds the suggestion of a drawing, of a carving, of so many mediums other than its own.

Anton Würth’s DürerÜbung II Nemesis, dated 2017, is the final print encountered in the exhibition. A two-colored engraving, the wall text alleges, but I only see muted grays. This piece is sparse. A singular line, curved and thin like string. A symmetrical spread of isolated rectangles with faint squiggles placed around them in an almost-grid. A column of six flat, vase-like shapes divide the print into two halves, framed by chess pieces on either side. Technically, this piece is advanced because it has curved lines, though you wouldn’t know that at first glance unless you know engravings. This print is meticulous but also odd, slightly off-putting. All its details present themselves instantly, yet I want to keep looking. Miya Tokumitsu’s curation choices elevate this piece. It’s the last one we encounter. It’s on the cover of the pamphlet. I feel its importance in its sparseness. It doesn’t need to ramble to convey its message. Its lines are all distinct, separate. It presents as though it has nothing to hide, but all the empty space signifies something inscrutable lurking beneath the surface. I feel there is something I don’t understand.

This exhibit tells a story of progress, but it also refuses linearity. It refutes the notion of art as constantly moving forward into new methods, innovative looks. The arrangement of this exhibit reflects this refusal. On the one hand, the space beckons to be traversed in a circle, clockwise, left-to-right. On the other hand, the categorizing labels are so missable, the gallery walls so close together. It’s easy to move backwards or in a jumbled route, easy to determine that this show has no progression, no order, because the order is not neatly chronological.

The titular wall text comes in the middle of the exhibition. This text is bizarre enough to prompt examination in its own right: “In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the titular prince declares time to be ‘out of joint’ after a visit from his father’s ghost–an event that sets off a cascade of moral and psychological crises. But knowledge from the past is not always an unwelcome intruder.” Here, the text calls on a past text and contradicts its message to argue that information from past works of art is important. Time blurs in this exhibit; it is “out of joint.” The exhibition welcomes out-of-jointness. Perhaps it even argues that engraving as a form disrupts the linearity of time. An engraving entitled “Portrait of Félix Vialart, Évêque-Comte de Châlons” sits next to the wall text. It shows a seventeenth-century portrait which was reworked first in 1867 and then again in 2021 by Anton Würth, who added polka dots and other playful embellishments to this very serious portrait. In engraving, one can ink a plate again and again. One can rework a plate again and again. These centuries become one, direction becomes meaningless—until you step forward a few feet, read “New Directions” on the wall, and wonder if that means the other directions must be old.

This exhibition values tradition but also innovation. It does not try to undo this contradiction but rather revels in its ambiguity. Miya Tokumitsu’s curatorial decisions appreciate the strength of time’s pull forward but also embrace the fickleness of time, the ways it can also pull us backwards, can twist us out of joint. So we inch along, up and down, moving ahead, glancing slowly back and forth, watching the world and its art change in ways that are not always progressions. Up and down. Round and round.