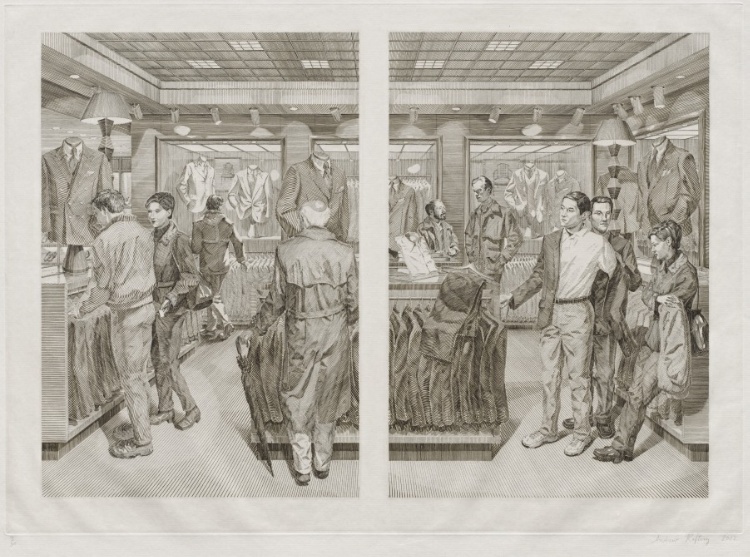

Raftery, Andrew. “Suit Shopping: An Engraved Narrative,” 2002-2003.

by Sarah Liu

Wesleyan University’s Davison Art Collection has one of the most robust print collections of all American universities. Home to over twenty-five thousand works of art, their print collection spans from woodcuts to lithographs to monotypes. But Pruzan Art Center’s newest exhibit, “Engraving after 1900: A Technique in Its Time,” spotlights a method of printmaking often caught in the crossfire of the push towards modernism and the avant-garde. Innately laborious and practical, engraving has historically been associated with metal workmanship and seen as a craft or skill, not fully afforded the prestige of the more conceptual and personal

fine art.

Comprised of five subsections and a sixth larger one themed around sugar, “Engraving after 1900” showcases the work of two dozen artists, a sizable portion of which practiced at Atelier 17, a print studio founded in the 1920s by Stanley William Hayter (who himself has two pieces in the exhibition). As the exhibition’s accompanying publication outlines, Atelier 17 functioned as a venue for many “canonical figures of twentieth-century modernism” and encouraged its artists to follow their specific artistic sensibilities rather than conform to one movement or style. This principle comes through in this exhibition in the range of work by Atelier 17 artists — Norma Morgan’s shadowy landscapes, the architectural eye evident in Armin Landeck’s angular lines, and the abstract figures of Dorothy Dehner. The only requirement was to afford appropriate respect and dedication to printmaking as an art form, to “[take] it seriously.”

It would come as a disappointment, then, that “Engraving after 1900” fails to impart that very idea on its viewers, mainly because of the context of the gallery space itself. While the philosophy of Atelier 17 as an organization was to promote engraving as an art form, so is the exhibition — the gallery introduction text and exhibition publication both emphasize how engraving has long been overlooked and underappreciated. But the absence of descriptive labels for the engravings themselves and inventive ways to convey the labor of the process make the exhibition fall flat to the average university student.

The Pruzan Art Center is a small nook in the Center for Public Affairs building. While Pruzan is open to the public, the entire building is predominately used by students. Hundreds of students — all studying different subjects — flock to the building every day to attend class, study, and drop into professor office hours. As such, the vast majority of visitors to Pruzan are students, and they’re students who aren’t necessarily into art. So the question arises of how to make engraving, of which many visitors most likely have a rudimentary understanding, accessible. Better yet, compelling.

There are some parts of “Engravings after 1900” that shine: the five subsections are topical to the exhibition’s examination with engravings’ role in modernism (particularly “New Directions” and “The Natural World”), and some pieces are adequately contextualized. James Louis Steg’s “Self Analysis” (1948) employs linework narratively and beautifully, etching a portrait of a man stoic and resigned. Its accompanying label informs the viewer that Steg served in the U.S. army during World War II, part of a tactical unit comprised of “artistically inclined soldiers…tasked with devising creative methods of confounding the enemy.” This added context renders the engraving in subtext; we begin to imagine the shading on his cheek as not a shadow or facial hair, but possibly the vestiges of war. The laborious and innate violent nature of engraving adds another layer to the heavy connotations of war — we then understand the work’s cruciality as an engraving print, rather than a lithograph print or painting.

In contrast, Andrew Raftery’s set of four engravings, titled “Suit Shopping: An Engraved Narrative” (2002-2003), is only labelled with the standard information of a gallery label: the piece’s title and the artist’s name. While the prints are meticulous, engrossing, and wonderfully lucid — one could argue their complexity warrants the lack of context — they would be enhanced by more information. Or at least some description that tied the suit-shopping action portrayed in the print to the sociological and how that impacts engravings’ conversations with modernity.

A more dynamic way to draw novice visitors into the art form of engraving is to invite elements of the process into the gallery, alongside the art. While the prints are the finished product, the process is arguably as important in a form as physical as this. As Hayter said while defending engraving’s relevance to modernity’s preoccupation with the unconscious, the labor of engraving is a reciprocal “exchange between the work and the person doing it. What the plate is doing to you and not what you are doing to the plate only.” So, why not highlight the labor itself? Physical burins and copper plates should be displayed, videos or live demos of the etching and ink transfer processes could be played, and a step-by-step visual guide foregrounded, in a physical manifestation of the “The Engraving Process” section of the exhibition publication. Not only would these changes demystify the engraving process to students (again, the average viewer in this context), but they would also make it tactile and interactive.

The most disjointed element of “Engravings after 1900” is its sixth and final section, “The Fascination of Sugar.” Tonally dissonant and physically removed from the other five sections in a semi-separate room, this section is also artistically divergent from the others, incorporating color prints for the first time and comprised of prints in a more pop-art style. While there is a historical explanation about sugar’s “enticing” and “enthralling” qualities, it is unclear why sugar was chosen as the theme for this last section, which makes it read as random and a possible half-hearted attempt to appeal to a younger audience. To make engraving interesting to undergraduate students means portraying it in all its complexity, not cheapening it with a topical gimmick. Ultimately, I’m not suggesting a degradation or oversimplification of the exhibition form, but merely an adaptation of it for a university student population.